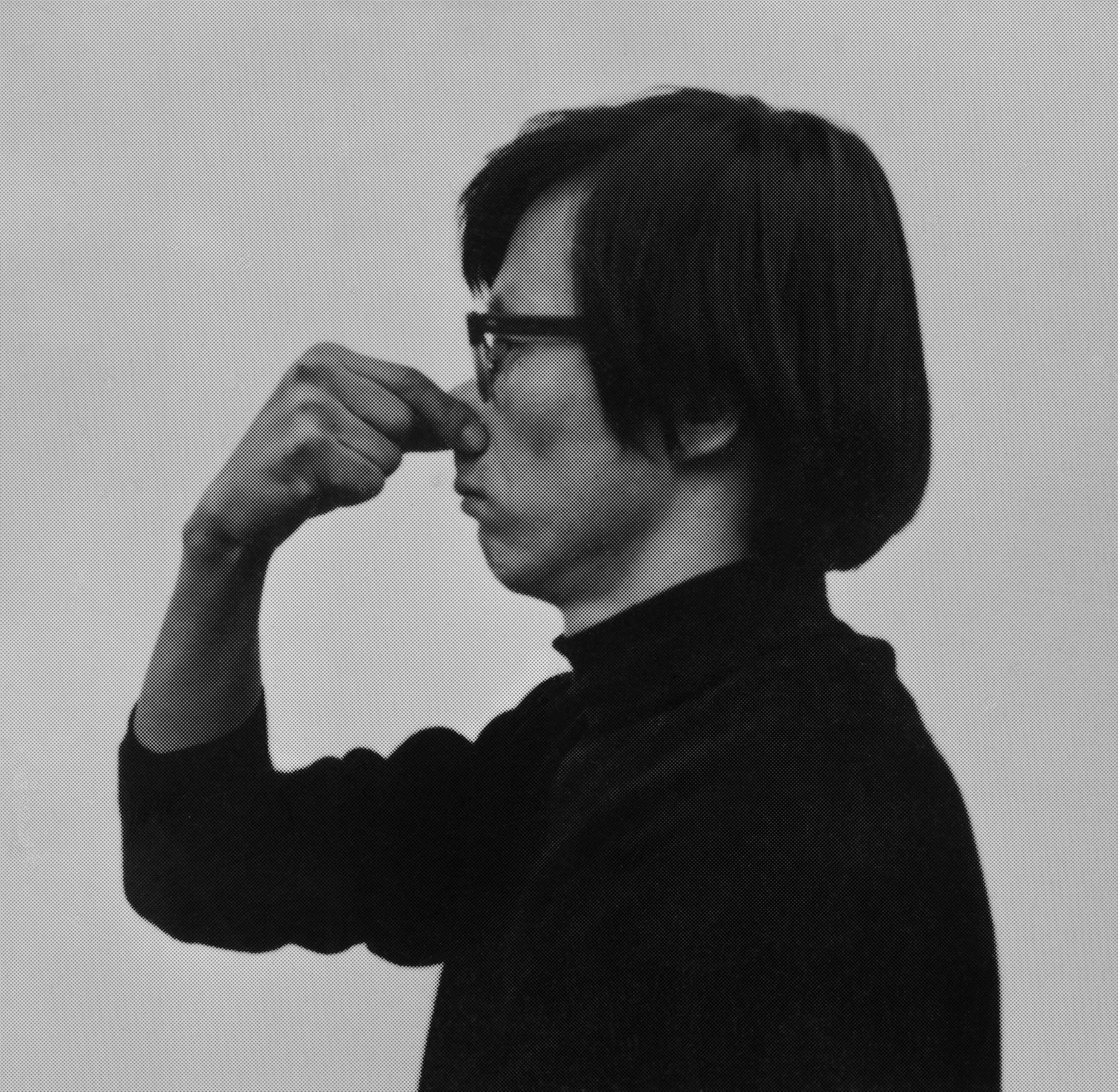

Lee Kun-Yong’s work begins from refusal. At a moment when artistic meaning in Korea was frequently reduced to expression or political signal, he chose neither — and replaced both with procedure. Instead, he established rules — clear, limited, repeatable — and carried them out through the body.

What emerges is not performance in the theatrical sense, but execution under constraint. The body does not express. It operates as a system.

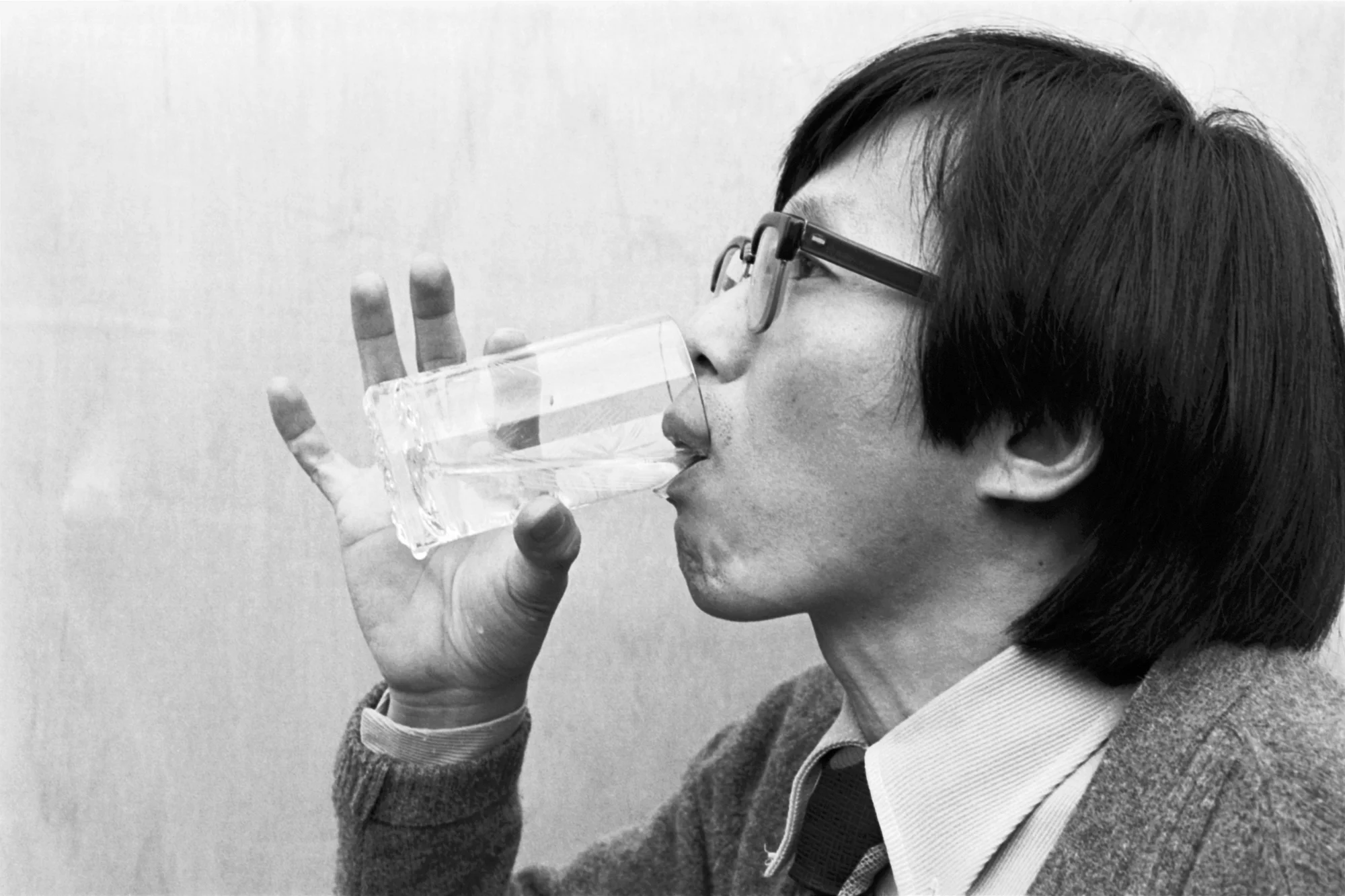

Drinking Water (1975/2026) consists of a sequence of photographs documenting a simple action: the artist lifting a glass, drinking, returning the glass to the table. Nothing is emphasized. Nothing accumulates. Each image remains strictly equivalent to the last. The action does not build toward a conclusion. It ends only because it stops.

Walking, eating, measuring, raising a hand — these actions recur across the early works. Their significance does not lie in gesture, but in consistency as validation. Each work begins with a condition that determines what can occur and ends without resolution. Nothing is improved, completed, or exhausted. The action simply confirms that the system holds.

Lee later referred to these works not as performances but as Events, and later still as Logical Events. An event unfolds according to internal necessity rather than improvisation or response. Repetition is not expressive emphasis, but testing. Meaning does not develop here; it is deliberately suspended.

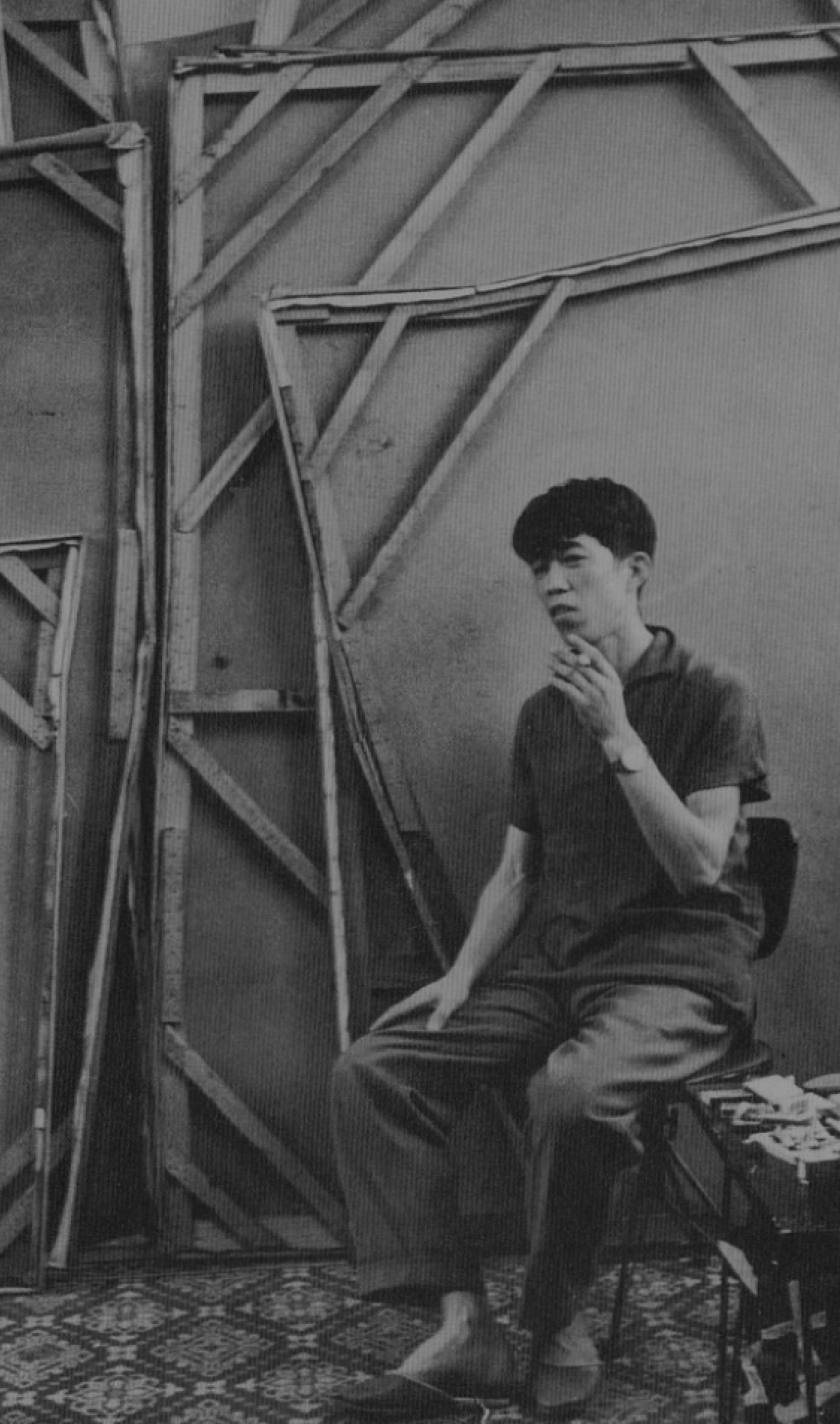

Snail’s Gallop (2022) records the trace of a crouching body moving forward in measured increments. The brush does not describe speed or effort. It registers constraint. Progress occurs slowly, under pressure, without flourish. Each panel maintains the same logic, differing only in duration. No image resolves what the previous one began.

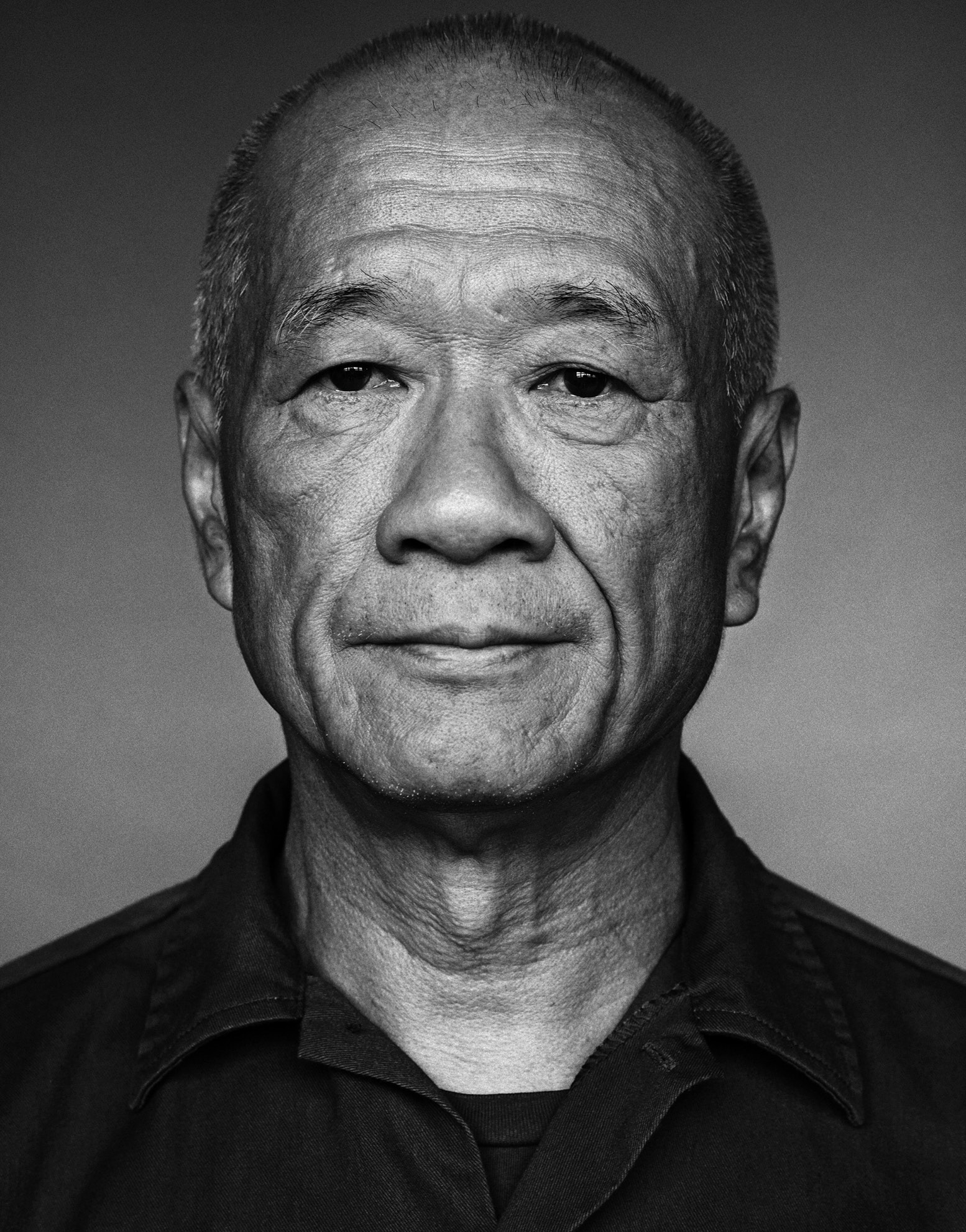

Across decades and media, the materials change — photographic documentation, instruction-based actions, large-scale paintings — but the role of the body does not. It reappears not as a site of expression, but as an instrument: disciplined, precise, capable of carrying structure without embellishment.

In the later Bodyscape paintings, the body dissolves into repeated, regulated gestures. The strokes fan outward only as far as the system allows. What becomes visible is not motion, but limit as condition.

The work does not ask to be interpreted. It asks only that its conditions be followed — so that its logic can continue intact.