While Zammitt is frequently linked to California Light and Space, his work functions structurally: color acts as measure, not atmosphere. These paintings regulate perception through interval and calibration.

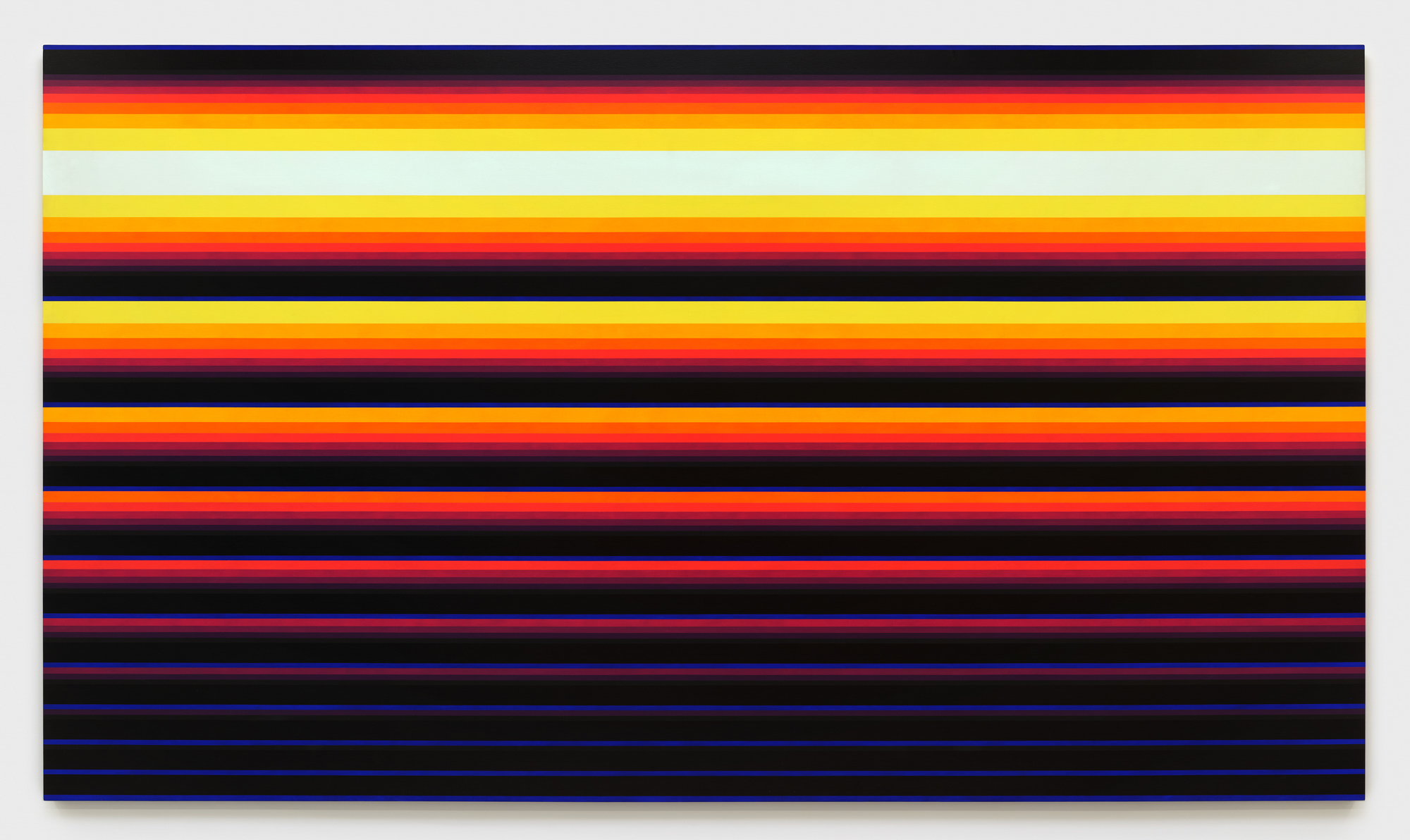

In One (1973), color moves upward in narrow horizontal bands, beginning in near-black before loosening gradually into yellow. The shift is slow enough that contrast never announces itself. No single register asks to be noticed. Difference is distributed across the surface rather than concentrated.

The bands are not sequential. They behave as measures. Each strip adjusts to the one beside it, introducing change without escalation. The surface does not open into depth or sensation. Nothing tips perception out of calibration.

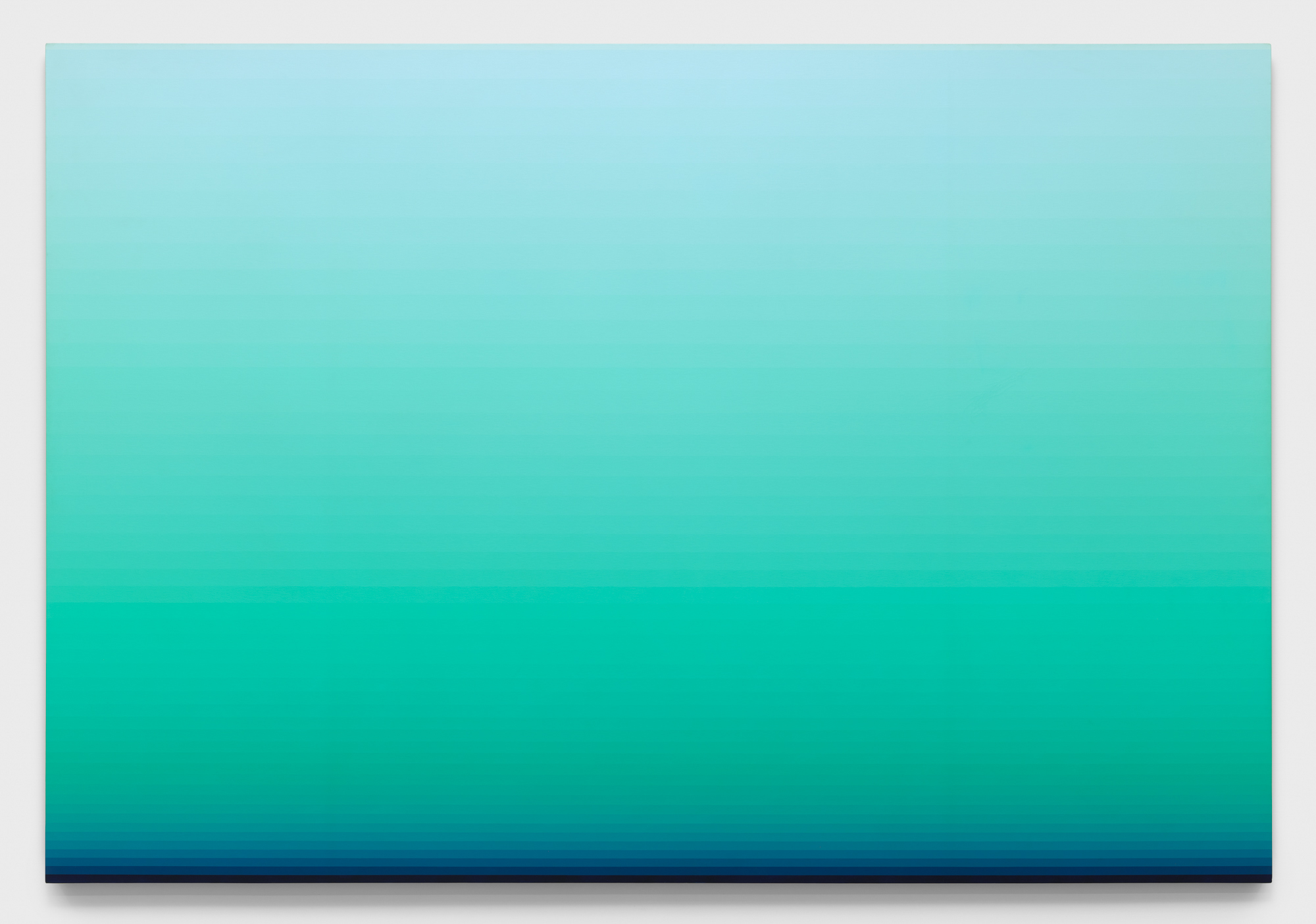

That same logic governs Green One (1975), where transitions are stretched even further. Color moves so incrementally that borders begin to dissolve before they fully form. Looking slows—not because the image overwhelms, but because no transition completes. Perception stays active without being directed.

The smaller Band Paintings make this calibration easier to register. Scaled down, the system tightens. Intervals shorten. Differences become more legible without turning emphatic. Color behaves less like field than like unit—measured, adjusted, and held.

The laminated acrylic poles introduce a vertical counterpoint. In works from the late 1960s, narrow planes of colored acrylic are stacked into tall, leaning forms. Transparency no longer produces depth. It redistributes weight. Color is encountered edge-first, layer by layer, through thickness rather than surface.

Looking shifts accordingly. Attention moves between hue and alignment, between material density and spacing. The poles don’t dramatize light; they regulate how it is received, just as the paintings do across the wall.

These bodies of work are connected by method rather than material or format. In both, color is not used to produce atmosphere or emotion. It establishes proportion—determining how much change can occur before perception begins to tip.

In North Wall (1976), this restraint becomes architectural. Bands stretch across a scale large enough to engage the body, yet the effect remains measured. The surface does not envelop. It holds its position. The painting sustains a condition rather than creating an environment.

Across the works, nothing builds. No moment intensifies. Time does not unfold; it steadies. Perception remains active without being led toward meaning or resolution.

Light here is not treated as phenomenon.

It is treated as measure.